ORIGINS

At the heart of the history of the ancient Moors of the Sahara is a tribe known as the Garamantes. According to E. W. Bovill, ethnologically the Garamantes are not easy to place,  but we may presume them to have been negroid.

but we may presume them to have been negroid.

Their homeland was in the area later known as the Fezzan in the Sahara; their capital city, called Garama or Jerma, lay amidst a tangle of

trading routes connecting the ancient cities of Ghat, Ghadames, Sabaratha,

Cyrene, Oea, Carthage and Alexandria. Far from being the obscure nomadic

community stereotyped in European literature, the Garamantes were one of

the most redoubtable and intimidating forces of the Sahara. The origins of Garamante culture are not easily traced.

Rock engravings and paintings done by early Saharans, who in all probability became the Garamantes, are difficult to date, but some believe the oldest were executed before 5000 B.C. These rock paintings show domesticated cattle, men riding in horse-drawn chariots, and javelin-armed men riding horses and camels.

There are over 300 representations of men in horse-drawn chariots alone, a

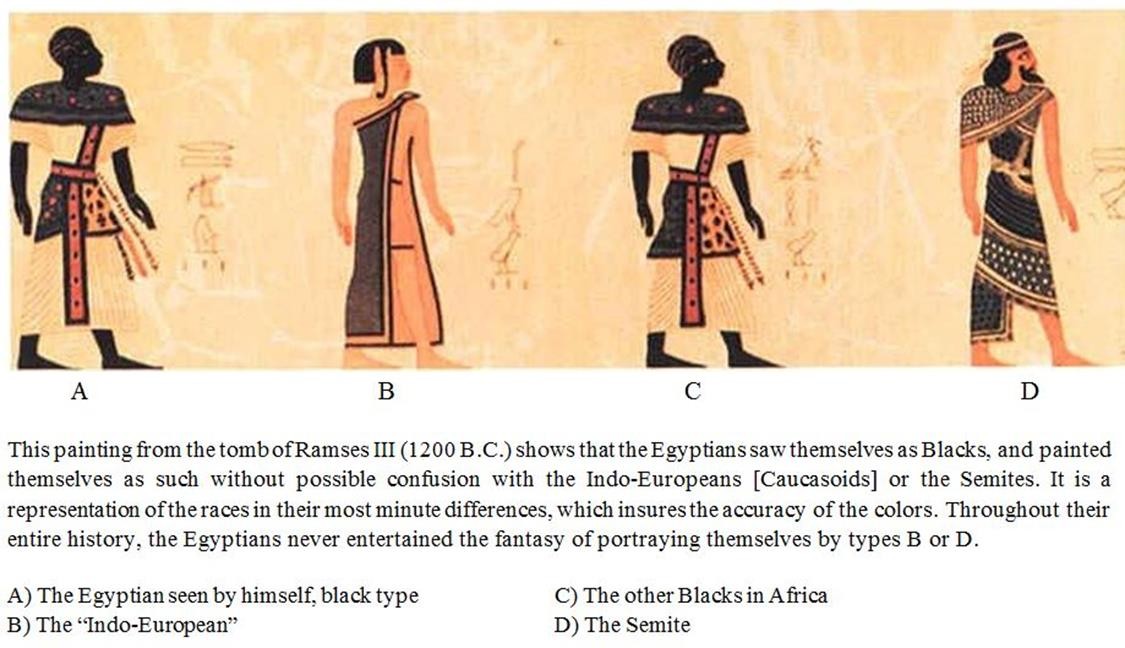

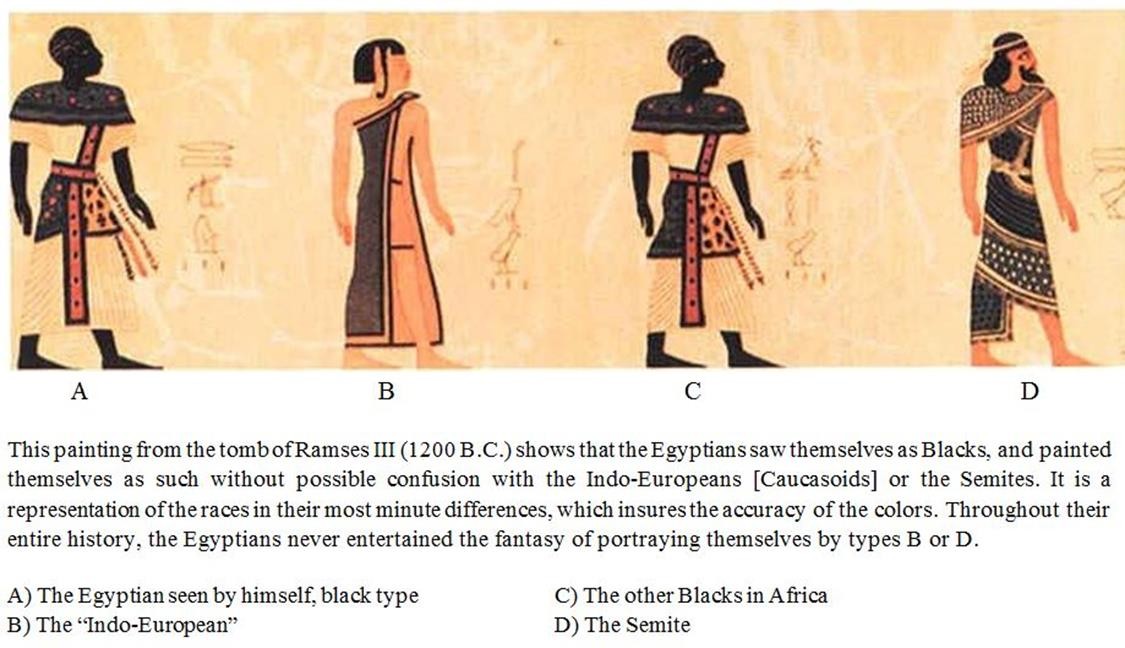

fact which supports Herodotus’ description of the fabulous Garamantes. According to E. W. Bovill, “some paintings give clear evidence of Egyptian

influence.” They include weapons and dress drawn in great detail as well as images of strange dieties. The Garamantes, or their predecessors, occupied much of northern Africa and were contemporary with the ancient Egyptian civilizations. From this vantage point, they can be considered the ancestors of the true Moors.

The earliest mention of the Garamantes themselves comes from Herodotus, who described them in the 5th century B.C. as being absorbed in a

rather sedentary lifestyle. However their endeavors in agriculture and commerce

had already made them “very powerful. In the second century B.C. Lucien noted their habits to be far from sedentary, they were “nomads and

dwellers in tents who made seasonal migrations into the remote south . . . They comprised tribes which dwell in towns and villages, and others which

were pastoral and nomadic Perhaps in order to protect their trade, they

developed military prowess to complement their economic power.

By the first century A.D., Tacitus called them “invincible”

, and Rome was in time to learn how powerful they really were. Unable to subdue the Garamantes, they actually joined them for several trading and exploratory expedition. Again, according to Tacitus, the territory they controlled by that time constituted the lion’s share of north central Africa; “their home country ... in the heart of the Sahara . . . but their territory and inhabitants occupied the perimeter of the Syrtic Coast and to the southeast it is said their range extended to the Nile. Contemporary with the Garamantes was another group called the Libyans.

The Libyans, however, were originally Caucasian troglodytes who occupied

territory in the far north central portion of Africa. Their presence has been

documented since the first dynasty in Egypt, circa 3100 B.C. Dr. Rosalie

David, an Egyptologist, describes them as “people with distinctive red or blond hair and blue eyes who lived on the edge of the western desert bordering Egypt. According to Gerald Massey, the Egyptians called the Lybians Tamahu. “In Egyptian, Tama means people and created. Hu is white, light ivory. Tamahu are the created white people. The Libyans role in that illuminated epoch of African history was to provide a constant irritant to lower Egypt. Several border skirmishes took place, culminating in extensive raiding during the 6th Dynasty. As DuBois notes, “there came great raids upon the Libyans to the west of Egypt.

Tens of thousands of soldiers, negros particularly from the Sudan, beat this part of the land into subjection.” Sethos, a Pharaoh in the 18th Dynasty, again confronted the Libyan foe and subdued them.

an Egyptologist, describes them as “people with distinctive red or blond hair and blue eyes who lived on the edge of the western desert bordering Egypt. According to Gerald Massey, the Egyptians called the Lybians Tamahu. “In Egyptian, Tama means people and created. Hu is white, light ivory. Tamahu are the created white people. The Libyans role in that illuminated epoch of African history was to provide a constant irritant to lower Egypt. Several border skirmishes took place, culminating in extensive raiding during the 6th Dynasty. As DuBois notes, “there came great raids upon the Libyans to the west of Egypt.

Tens of thousands of soldiers, negros particularly from the Sudan, beat this part of the land into subjection.” Sethos, a Pharaoh in the 18th Dynasty, again confronted the Libyan foe and subdued them.

The amalgamation of the Libyans with other races may be attributed to several different factors. Surrounded by darker people on all sides but the Mediterranean Sea, the fair-skinned Libyans constituted a small minority

within the black African continent. In addition, nomads of the Arabian Plate

fled their barren and drought-stricken homeland in search of more fertile lands to occupy. The blending of black Arab and Libyan produced a light brown or olive-skinned people who came to be known as “tawny Moors” or white Moors,” often known in history as the “Berbers.” The word Berber had

its base in a Roman expression “barbari .” When the Romans encountered the Libyans they referred to them as barbarians and the coastal region they oc- cupied later came to be known as the “Barbary Coast.” The Arabs later adopted the term and changed it to Berber. Eventually, the words Libyan and

Berber became synonymous.

Another factor in the racial blending of Lybians and so-called blacks was the roman intervention along the northern coast which forced thousands of these Berbers into the desert seeking protection and aid from its indigenous black

inhabitants. The alliance of these racially different groups laid the foundation

for the racial diversity which in later centuries would characterize the Sahara.

As E. W. Bovill notes, “The Romans . . . antagonized the tribes of the northern Sahara and the desert became both a refuge and a recruiting ground for all who rebelled against Rome. The best documented example of this is that of Tacfarinas, a Roman-trained Libyan soldier, who appealed to the Garamantes

for aid in 17 A.D. According to Bovill, “for several years Tacfarinas successfully defied the alien overlords during which time he was twice compelled

to seek refuge in the desert. On the second occasion, if not the first, it was the Garamantes who gave him shelter. Bovill also speaks of a Berber tribe known as the Zenta who, under Roman military pressure, migrated into deeper areas of the Sahara. So in time the Sahara came to be occupied by two distinct groups of people:

the original Maurs or Moors and the Berbers who later became Tawny Moors.

The rest of North Africa, from Egypt through the Fezzan and the west of the Sahara to “Mauretania” (Morocco and Algeria) were peopled by black Africans, also called Moors by the Romans and later by the Europeans.

(Morocco and Algeria) were peopled by black Africans, also called Moors by the Romans and later by the Europeans.

Eventually, these Moors would join with Arabs and become a united and

powerful force. A period of cultural dormancy, characterized by the treachery

and violence of tribal rivalry, concluded in the 6th century A.D. when a commanding and mystic figure arose from Arabia. Known as the prophet

Mohamet, he brought religious and cultural cohesiveness to the sword-wielding nomads of the Sahara, as he had done in his native land. “The prophet

Mohamet turned the Arab tribes, . . . into the Moslem people, filled them with

the fervour of Martyrs, and added to the greed of plunder the nobler ambition

of bringing all mankind to the knowledge of the truth.

Arabia itself had first been populated by black people. As Drusilla Houston

states in her classic text, Wonderful Ethiopians of the Ancient Cushite Empire, the Cushites were the original Arabians . . .,” for Arabia was the oldest Ethiopian colony. According to Houston, ‘‘Ancient literature assigns their first settlement to the extreme southwestern point of the peninsula. From thence

they spread northward and eastward over Yemen, Hadramaut and Oman. In fact the Ancient Greeks make no distinction between the mother country and her colony, calling them both “Ethiopia”.

Houston uses linguistics and physiognomy to support her contention. “A proof that they [the original Arabs] were Hamites [descendants from the Biblical Ham, from whom the black race is said to have sprung] lay in the name Himyar, or dusky, given to [those that were] the ruling race. The Himyaritic language, now lost, but some of which is preserved, is African in origin and character. Its grammar is identified with the Abyssinian” (Abyssinia being another name for Ethiopia). Finally, Houston quotes the Encyclopedia Britannica's article on Arabia; “The inhabitants of Yemen, Hadramaut, Oman and the adjoining districts [in Arabia], in shape of head, color, length and slenderness of limbs and scantiness of hair, point to an African origin. Stone engravings thousands of years old as well as modern photographs of Arabians bear testimony to the black African characteristics bequeathed Arabia by the original Arabians, the Cushite Ethiopians. According to Houston, “The culture of the Saracens and Islam arose and flourished from ingrafting Semitic blood upon the older Cushite root. As may be expected, W. E. B. DuBois makes some interesting points regarding the use of the word “Arab.” Having noted that many Arabs are “darkskinned, sometimes practically black, often have Negroid features, and hair that may be Negro in quality,” DuBois reasons that “the Arabs were too nearly akin to Negros to draw an absolute color line

Finally, DuBois concludes that the expression Arab has evolved into a definition that is more religious than racial. “The term Arab is applied to any people professing Islam, . . . much race mixing has occurred, so that while the term has a cultural value it is of little ethnic significance and is often misleading. In his native Arabia, Mohamet rallied great numbers of warriors and set out to subdue the east. Mohamet’s death in 632 A.D. did not stop the tremendous onslaught of his Arabian knights. They would eventually reach west to the Atlantic Coast of Africa, northwest to France and Spain, north to Russia and east to India. The jihads or crusades through north Africa claimed Egypt in 638, Tripoli in 643 and southwest Morocco in 681. With the bulk of north Africa united in the name of Allah, Mohamet’s followers looked north to Iberia, “land of rivers,” now known as Spain and Portugal. The Arab followers of Mohamet had found converts among the African Moors, both black and tawny, and both Arab and Moorish officers were later to lead the predominantly Moorish soldiers into Iberia. In fact, the followers of Mohamet amassed their greatest armies and some of their most outstanding military leaders from the Moors.

but some of which is preserved, is African in origin and character. Its grammar is identified with the Abyssinian” (Abyssinia being another name for Ethiopia). Finally, Houston quotes the Encyclopedia Britannica's article on Arabia; “The inhabitants of Yemen, Hadramaut, Oman and the adjoining districts [in Arabia], in shape of head, color, length and slenderness of limbs and scantiness of hair, point to an African origin. Stone engravings thousands of years old as well as modern photographs of Arabians bear testimony to the black African characteristics bequeathed Arabia by the original Arabians, the Cushite Ethiopians. According to Houston, “The culture of the Saracens and Islam arose and flourished from ingrafting Semitic blood upon the older Cushite root. As may be expected, W. E. B. DuBois makes some interesting points regarding the use of the word “Arab.” Having noted that many Arabs are “darkskinned, sometimes practically black, often have Negroid features, and hair that may be Negro in quality,” DuBois reasons that “the Arabs were too nearly akin to Negros to draw an absolute color line

Finally, DuBois concludes that the expression Arab has evolved into a definition that is more religious than racial. “The term Arab is applied to any people professing Islam, . . . much race mixing has occurred, so that while the term has a cultural value it is of little ethnic significance and is often misleading. In his native Arabia, Mohamet rallied great numbers of warriors and set out to subdue the east. Mohamet’s death in 632 A.D. did not stop the tremendous onslaught of his Arabian knights. They would eventually reach west to the Atlantic Coast of Africa, northwest to France and Spain, north to Russia and east to India. The jihads or crusades through north Africa claimed Egypt in 638, Tripoli in 643 and southwest Morocco in 681. With the bulk of north Africa united in the name of Allah, Mohamet’s followers looked north to Iberia, “land of rivers,” now known as Spain and Portugal. The Arab followers of Mohamet had found converts among the African Moors, both black and tawny, and both Arab and Moorish officers were later to lead the predominantly Moorish soldiers into Iberia. In fact, the followers of Mohamet amassed their greatest armies and some of their most outstanding military leaders from the Moors.

An Arab general named Musa Nosseyr was appointed Governor of Northern Africa in 698 A.D.  Although he cast covetous eyes towards Iberia, he

hesitated, knowing that a campaign on Iberia could exhaust his armies. The

Visigoths, who had earlier toppled the Roman Empire in Iberia, had ruled for over two hundred years. The Visigoths were a vigorous, rather barbaric people

who, as Christians, believed in religious compensation for their vices. Over

time they had become “quite as corrupt and immoral as the Roman nobles

who had preceded them.

Although he cast covetous eyes towards Iberia, he

hesitated, knowing that a campaign on Iberia could exhaust his armies. The

Visigoths, who had earlier toppled the Roman Empire in Iberia, had ruled for over two hundred years. The Visigoths were a vigorous, rather barbaric people

who, as Christians, believed in religious compensation for their vices. Over

time they had become “quite as corrupt and immoral as the Roman nobles

who had preceded them.

Although it is generally assumed that the movement of Africans into Europe, in significantly large numbers and into positions of real power, did not occur

until the Muslim invasion of Spain in 711 A.D.

In Al-Makkary ’s History ofthe Mohammedan Dynasties'in Spain , however, we learn of a great drought that afflicted Spain about three thousand years ago, a catastrophe that was fol- lowed not long afterwards by an invasion from Africa. This, of course, had nothing to do with the medieval Moors.

Yet another obstacle stood between Musa and Iberia. An outpost of the Greek Empire, the fortress of Ceuta, rested on the northern tip of Morocco.

This door to Iberia was guarded by Count Julian, an ally of Roderick, ruler of

Iberia. Count Julian fought off all Arab/Moorish attacks, and his fortress remained impregnable until Julian, for personal reasons, switched his alle- giance from Roderick of the Visigoths to Musa Nosseyr of the Moors.

Tradition has it that Roderick, while responsible for Julian’s daughter’s

welfare during her training at his court, broke his trust and took advantage of her sexually. Julian, furious at this betrayal, quickly reclaimed his daughter and sought out Musa. Julian proclaimed to the Arab governor his intent totally himself completely with Musa for the purpose of conquering the rich lands of Spain. He offered his own ships along with his knowledge of

Roderick’s defenses. While consulting with his Khalif, Musa sent an exploratory mission, of five hundred soldiers led by the black Moor Tarif.

After the reconnaissance mission returned, a success, in July of 710, Musa prepared to conquer Spain in earnest. Sources indicate that Musa selected another black Moor to lead the attack on Spain. DuBois writes “Tarik-bin-Ziad . . . became a great general in Islam and was the conqueror of Spain as the commander of the Moorish army which invaded Spain.” Stanley Lane-Poole, author of The Moors in Spain, also makes reference to “the Moor Tarik with 7000 troops, most of whom were also Moors [were sent] to make another raid . . .” On April 30, 711 A.D., Tariq crossed the straits of Hercules with his 7000 men, of which “6700 [were] native [Moorish] Africans and 300 [were] Arabs.” After landing on the Spanish coast, Tariq seized a great cliff and a portion of land around it. Deeming it strategically important, he directed the building of a fortress on the site. Tradition holds that his men named the fortress after him out of admiration and respect. The name Gabel Tariq, or General Tariq, was later corrupted to “Gibraltar”, and its fortress known as the “Rock of Gibraltar.” Tariq, leaving his fortress, ventured on to capture

Algeciras and Carteya.

Along his way through the country-side, he found

many Spanish natives eager to join him against the ruling Visigoths. His army,

rather than diminishing through attrition, actually swelled in size. “On 18th July of the same year, 711, Tariq with about 14,000 troops engaged Roderick at the head of some 60,000 troops at the Janda Lagoon by the mouth of the

Barbate.” Before the battle, knowing they were greatly outnumbered, Tariq

addressed his solders: “My men, whither can you flee? Behind you lies the sea and before you the foe. You possess only your courage and constancy for you

are present in this country poorer than orphans before a greedy guardian’s

table. It will be easy to turn this table on him if you will but risk death for one instance."

It will be easy to turn this table on him if you will but risk death for one instance."

It's has been some dispute over the race (color) of the Moors , but there can be no doubt that the Almoravid Dynasty was purely of African (negroid) orgins.

These Saharan Berbers were inspired to improve their knowledge of Islamic doctrine by their leader Yaḥyā ibn Ibrāhīm and the Moroccan theologian ʿAbd Allāh ibn Yasīn. Under Abū Bakr al-Lamtūnī and later Yūsuf ibn Tāshufīn, the Almoravids merged their religious reform fervour with the conquest of Morocco and western Algeria as far as Algiers between 1054 and 1092. They established their capital at Marrakech in 1062. Yūsuf assumed the title of amīr al-muslimīn (“commander of the Muslims”)

but still paid homage to the ʿAbbāsid caliph (amīr al-muʾminīn, “commander of the faithful”) in Baghdad. He moved into Spain in 1085, as the old caliphal territories of Córdoba were falling before the Christians and Toledo was being taken by Alfonso VI of Castile and Leon. At the Battle of Al-Zallāqah, near Badajoz, in 1086 Yūsuf halted an advance by the Castilians but did not regain Toledo.

The whole of Moslem and Muslim Spain, however, except Valencia, independent under El Cid (Rodrigo Díaz de Vivar), eventually came under Elmoravid rule. In the reign (1106–42) of ʿAli ibn Yūsuf the union between Spain and Africa was consolidated, and Andalusian civilization took root: administrative machinery was Spanish in pattern, writers and artists crossed the straits, and the great monuments built by ʿAlī in the Maghrib were models of pure Andalusian art. But the Elmoravids were but a

Berber minority at the head of the Spanish-Arab empire, and, while they tried to hold Spain with Berber troops and the Maghrib with a strong Christian guard, they could not restrain the tide of Christian reconquest that began with the fall of Saragossa in 1118. In 1125 the Almohads began a rebellion in the Atlas Mountains and after 22 years of fighting emerged victorious. Marrakech fell in 1147, and thereafter Almoravid leaders survived only for a time in Spain and the Balearic Isles.

Noble Murabitun's

Abu Bakr ibn Umar

(1056 - 1087) | – partitioned reign from 1072

Abu Bakr ibn Umar was a member of the Banu Turgut, a clan of the Lamtuna Berbers. His brother, Yahya ibn Umar al-Lamtuni was the chieftain of the Lamtuna who, together with the Maliki teacher Abdallah ibn Yasin, launched the Almoravid

(murabitūn) movement in the early 1050s.

Upon the death of Yahya ibn Umar in the spring of 1056 at the Battle of Tabfarilla, the spiritual leader Abdallah ibn Yasin appointed Abu Bakr as the new military commander of the Almoravids. That same year, Abu Bakr recaptured Sijilmassa from

the Maghrawa of the Zenata confederation. The city had been taken earlier by Yahya, but subsequently lost; Abu Bakr recaptured it definitively for the Elmoravids in late 1056.

In order to ensure they did not lose Sijilmassa again, Abu Bakr launched a campaign to secure the roads and valleys of southern Morocco. He immediately captured the Draa valley, then moved along the Wadi Nul (along the edge of the Anti-Atlas,

picking up the adherence of the Sanhaja tribes of the Lamta and the Gazzula (Jazzula) to the Almoravid movement. Abu Bakr led the conquest of the Sous valley of southern Morocco, seizing the local capital of Taroudannt in 1057. By negotiation,

Abdallah ibn Yasin secured an alliance with the Masmuda Berbers of the High Atlas, which allowed the Elmoravids to cross the mountain range with little incident and seize the critical Zenata-ruled citadel of Aghmat in 1058 with little opposition.

Delighted at the apparent ease of their advance, Abdallah ibn Yasin ventured into the lands of the Berghwata of western Morocco with only a light escort and was promptly killed. Abu Bakr, who was then mopping up the area north of Aghmat, wheeled

the Elmoravid army around and conquered the Berghwata in a brutal campaign of revenge.

The death of the spiritual leader Abdallah ibn Yasin left the Elmoravids under the sole command of Abu Bakr. Abu Bakr continued carrying out the Elmoravid program without assuming the pretence of religious authority in himself. Abu Bakr, like

later Elmoravid rulers, took up the comparatively modest title of amir al-Muslimin ("Prince of the Muslims"), rather than the caliphal amir al-Mu'minin ("Commander of the Faithful").

Abu Bakr married the wealthiest woman in Aghmat, Zaynab an-Nafzawiyyah, who helped him navigate the complicated politics of southern Morocco. But Abu Bakr, a rustic desert warrior, found crowded Aghmat and its courtly life stifling. In 1060/61,

Abu Bakr and his Sanhaja lieutenants left the city and pitched their tents on the pastures along the Tensift River, setting up an encampment for their headquarters, as if they were back in the Sahara desert. Stone buildings would eventually

replace the tents, and the encampment would become the city of Marrakesh, an unusual-seeming city for the time, evocative of desert life with planted palms and an oasis-like feel.

Abu Bakr placed his cousin Yusuf ibn Tashfin in charge of Aghmat, and assigned him the responsibility of maintaining the front against the Zenata to the north. In a series of campaigns through the 1060s, while Abu Bakr held court in Marrakesh,

Yusuf directed Elmoravid armies against northern Morocco, reducing Zenata strongholds one by one. In 1070, the Moroccan capital of Fez finally fell to the Elmoravids. Discontent, however, had arisen in the Elmoravid ranks, particularly among the

desert clans back in the Sahara, who regarded these distant northern campaigns as expensive and pointless. The Guddala tribe, who had earlier broken away from the Elmoravid coalition, began urging other desert tribes to follow suit. After the

fall of Fez, feeling Morocco was now secure, Abu Bakr decided it was time to return to the Sahara to quell the dissension in the desert homelands. He placed Yusuf ibn Tashfin in charge of Morocco in his absence. As was common among the Sanhaja

tribes before extended military campaigns, Abu Bakr divorced Zaynab before he left, advising her to marry Yusuf if she needed protection.

Having quelled the discontent back in the Sahara, Abu Bakr returned north to Morocco in 1072. But Yusuf ibn Tashfin had enjoyed his taste of power, and was reluctant to give it up. Pushed by his new wife, Zaynab, Yusuf met Abu Bakr in the plain

of Burnoose (between Marrakesh and Aghmat) and, by negotiation (rather than force), persuaded him to abdicate the northern dominions to him. As a courtesy to his former leader, Yusuf kept Abu-Bakr's name on the Elmoravid coinage until his death.

Abu Bakr returned to the Sahara desert to command the southern wing of the Elmoravids. He launched a new set of campaigns against the dominions of the Ghana Empire in 1076 and is often credited with initiating the spread of Islam on the southern

periphery of the Sahara. His campaigns are said to have gone as far as Mali and Gao.

Abu Bakr ibn Umar died in 1087, and his dominions were partitioned among his sons and nephews (the sons of Yahya) after his death.

Mauritanian oral tradition claims Abu Bakr was killed in a clash with the "Gangara" (Soninke Wangara of the Tagant Region of southern Mauritania), relating that he was struck down by an arrow from an old, blind Gangara chieftain in the pass of

Khma (between the Tagant and Assab mountains, en route to Ghana). According to Wolof oral tradition, a Serer bowman named Amar Godomat killed him with his bow near lake Rzik (just north of the Senegal) (Godomat's name apparently originates with

this death). It goes on to note that Abu Bakr left a pregnant Fula wife, Fâtimata Sal, who gave birth to a son, the legendary Amadou Boubakar ibn Omar, better known as Ndiadiane Ndiaye, who went on to found the Wolof kingdom of Waalo in the lower

Senegal river.

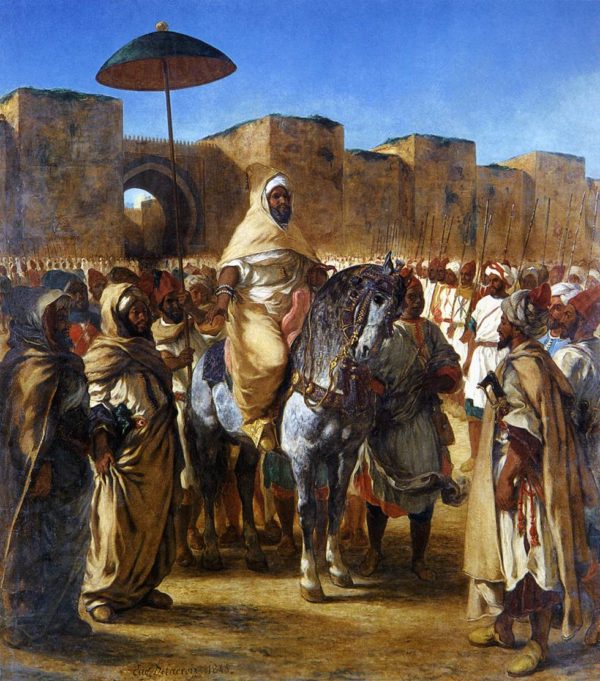

Yusuf ibn Tashfin

(1072 - 1106) |

Yusuf ibn Tashfin, also Tashafin, Teshufin, (Arabic: يوسف بن تاشفين ناصر الدين بن تالاكاكين الصنهاجي, romanized: Yūsuf ibn Tāshfīn Naṣr al-Dīn ibn Tālākakīn al-Ṣanhājī; reigned c. 1061 – 1106) was leader of the Berber Elmoravid empire. He

co-founded the city of Marrakesh and led the Muslim forces in the Battle of Sagrajas. Ibn Tashfin came to al-Andalus from Africa to help the Muslims fight against Alfonso VI, eventually achieving victory and promoting an Islamic system in the

region. In 1061 he took the title “amir al-Muslimin” recognising the suzerainty of the Abbasid Caliphate whom he became a vassal of. He was married to Zaynab an-Nafzawiyyah, whom he reportedly trusted politically.

Succession to power

Yusuf ibn Tashfin was a Berber from the Banu Turgut, a branch of the Lamtuna, a Tuareg tribe belonging to the Sanhaja group. The Sanhaja were linked by medieval Muslim genealogists with the Yemeni tribe of Himyar through semi-mythical and

mythical pre-Islamic kings and for some reason, some of the contemporary sources (e.g., Ibn al-Arabi) add the nisba al-Himyari to Yusuf's name to indicate this legendary affiliation. Modern scholarship rejects this Berber–Yemeni link as fanciful.

Abu Bakr ibn Umar, a natural leader of Lamtuna extraction, a branch of the Sanhaja, and one of the original disciples of ibn Yasin who served as a spiritual liaison for followers of the Maliki school of Islamic jurisprudence, was appointed chief

commander after the death of his brother Yahya ibn Umar al-Lamtuni. His brother oversaw the military for ibn Yasin but was killed in the Battle of Tabfarilla against the Godala tribes in 1056. Ibn Yasin, too, would die in battle against the

Barghawata three years later. Abu-Bakr was an able general, taking the fertile Sūs and its capital Aghmāt a year after his brother's death, and would go on to suppress numerous revolts in the Sahara--on one such occasion entrusting his pious

cousin Yusuf with the stewardship of Sūs and thus the whole of his northern provinces. He appears to have handed him this authority in the interim but even went as far as to give Yusuf his wife, Zaynab an-Nafzawiyyat, purportedly the richest

woman of Aghmāt. This sort of trust and favor on the part of a seasoned veteran and savvy politician reflected the general esteem in which Yusuf was held, not to mention the power he attained as a military figure in his absence. Daunted by

Yusuf's new-found power, Abu Bakr saw any attempts at recapturing his post politically unfeasible and returned to the fringes of the Sahara to settle the unrest of the southern frontier

Military exploits

Grand mosque, Algiers in 1840 - The mosque was established by Yusuf ibn Tashfin in the 11th century

Yusuf was an effective general and strategist who put together a formidable army comprising Sudanese contingents, Christian mercenaries and the Saharan tribes of the Gudala, Lamtuna and Masufa, which enabled him to expand the empire, crossing the Atlas Mountains onto the plains of Morocco, reaching the Mediterranean and capturing Fez in 1075, Tangier in 1079, Tlemcen in 1080, and Ceuta in 1083, as well as Algiers, Ténès and Oran in 1082-83. He is regarded as the co-founder of the famous

Moroccan city Marrakech (in Berber Murakush, corrupted to Morocco in English). The site had been chosen and work started by Abu Bakr in 1070. The work was completed by Yusef, who then made it the capital of his empire, in place of the former

capital Aghmāt. By the time Abu Bakr died in 1087, after a skirmish in the Sahara as the result of a poison arrow, Yusef had crossed over into al-Andalus and also achieved victory at the Battle of az-Zallaqah, also known as the Battle of Sagrajas

in the west. He came to al-Andalus with a force of 15,000 men, armed with javelins and daggers, most of his soldiers carrying two swords, shields, cuirass of the finest leather and animal hide, and accompanied by drummers for psychological effect.

Yusef's cavalry was said to have included 6,000 shock troops from Senegal mounted on white Arabian horses. Camels were also put to use. On October 23, 1086, the Elmoravid forces, accompanied by 10,000 Andalusian fighters from local Muslim

provinces, decisively checked the Reconquista, significantly outnumbering and defeating the largest Christian army ever assembled up to that point. The death of Yusef's heir, however, prompted his speedy return to Africa.

When Yusuf returned to al-Andalus in 1090, he saw the lax behavior of the taifa kings, both spiritually and militarily, as a breach of Islamic law and principles, and left Africa with the express purpose of usurping the power of all the Muslim

principalities, under the auspices of the Abbasid caliph of Baghdad, with whom he had shared correspondence, and under the slogan "The spreading of righteousness, the correction of injustice and the abolition of unlawful taxes." The emirs in such

cities as Seville, Badajoz, Almeria and Granada had grown accustomed to the extravagant ways of the west. On top of doling out tribute to the Christians and giving Andalusian Jews unprecedented freedoms and authority, they had levied burdensome

taxes on the populace to maintain this lifestyle. After a series of fatwas and careful deliberation, Yusef saw the implementation of orthodoxy as long overdue. That year, he exiled the emirs 'Abdallah and his brother Tamim from Granada and Málaga,

respectively, to Aghmāt, and a year later al-Mutamid of Seville suffered the same fate. When all was said and done, Yusef united all of the Muslim dominions of the Iberian Peninsula, with the exception of Zaragoza, to the Kingdom of Morocco, and

situated his royal court at Marrakech. He took the title of Amir al-muslimin (Prince of the Muslims), seeing himself as humbly serving the caliph of Baghdad, but to all intents and purposes he was considered the caliph of the western Islamic

empire. The military might of the Elmoravids was at its peak.

The Sanhaja confederation, which consisted of a hierarchy of Lamtuna, Musaffa and Djudalla Berbers, represented the military's top brass. Amongst them were Andalusian Christians and heretic Africans, taking up duties as diwan al-gund, Yusef's own

personal bodyguard, including 2,000 black horsemen, whose tasks also included registering soldiers and making sure they were compensated financially. The occupying forces of the Almoravids were made up largely of horsemen, totaling no less than

20,000. Into the major cities of al-Andalus, Seville (7,000), Granada (1,000), Cordoba (1,000), 5,000 bordering Castile and 4,000 in western al-Andalus, succeeding waves of horsemen, in conjunction with the garrisons that had been left there after

the Battle of Sagrajas, made responding, for the Taifa emirs, difficult. Soldiers on foot used bows & arrows, sabres, pikes, javelins, each protected by a cuirass of Moroccan leather and iron-spiked shields. During the siege of the fort-town Aledo,

in Murcia, previously captured by the Spaniard Garcia Giménez, ELmoravid and Andalusian hosts are said to have used catapults, in addition to their customary drum beat. Yusef also established naval bases in Cadiz, Almeria and neighboring ports

along the Mediterranean. Ibn Maymun, the governor of Almeria, had a fleet at his disposal. Another such example is the Banu Ghaniya fleet based off the Balearic Islands that dominated the affairs of the western Mediterranean for much of the 12th

century

The site had been chosen and work started by Abu Bakr in 1070. The work was completed by Yusef, who then made it the capital of his empire, in place of the former

capital Aghmāt. By the time Abu Bakr died in 1087, after a skirmish in the Sahara as the result of a poison arrow, Yusef had crossed over into al-Andalus and also achieved victory at the Battle of az-Zallaqah, also known as the Battle of Sagrajas

in the west. He came to al-Andalus with a force of 15,000 men, armed with javelins and daggers, most of his soldiers carrying two swords, shields, cuirass of the finest leather and animal hide, and accompanied by drummers for psychological effect.

Yusef's cavalry was said to have included 6,000 shock troops from Senegal mounted on white Arabian horses. Camels were also put to use. On October 23, 1086, the Elmoravid forces, accompanied by 10,000 Andalusian fighters from local Muslim

provinces, decisively checked the Reconquista, significantly outnumbering and defeating the largest Christian army ever assembled up to that point. The death of Yusef's heir, however, prompted his speedy return to Africa.

When Yusuf returned to al-Andalus in 1090, he saw the lax behavior of the taifa kings, both spiritually and militarily, as a breach of Islamic law and principles, and left Africa with the express purpose of usurping the power of all the Muslim

principalities, under the auspices of the Abbasid caliph of Baghdad, with whom he had shared correspondence, and under the slogan "The spreading of righteousness, the correction of injustice and the abolition of unlawful taxes." The emirs in such

cities as Seville, Badajoz, Almeria and Granada had grown accustomed to the extravagant ways of the west. On top of doling out tribute to the Christians and giving Andalusian Jews unprecedented freedoms and authority, they had levied burdensome

taxes on the populace to maintain this lifestyle. After a series of fatwas and careful deliberation, Yusef saw the implementation of orthodoxy as long overdue. That year, he exiled the emirs 'Abdallah and his brother Tamim from Granada and Málaga,

respectively, to Aghmāt, and a year later al-Mutamid of Seville suffered the same fate. When all was said and done, Yusef united all of the Muslim dominions of the Iberian Peninsula, with the exception of Zaragoza, to the Kingdom of Morocco, and

situated his royal court at Marrakech. He took the title of Amir al-muslimin (Prince of the Muslims), seeing himself as humbly serving the caliph of Baghdad, but to all intents and purposes he was considered the caliph of the western Islamic

empire. The military might of the Elmoravids was at its peak.

The Sanhaja confederation, which consisted of a hierarchy of Lamtuna, Musaffa and Djudalla Berbers, represented the military's top brass. Amongst them were Andalusian Christians and heretic Africans, taking up duties as diwan al-gund, Yusef's own

personal bodyguard, including 2,000 black horsemen, whose tasks also included registering soldiers and making sure they were compensated financially. The occupying forces of the Almoravids were made up largely of horsemen, totaling no less than

20,000. Into the major cities of al-Andalus, Seville (7,000), Granada (1,000), Cordoba (1,000), 5,000 bordering Castile and 4,000 in western al-Andalus, succeeding waves of horsemen, in conjunction with the garrisons that had been left there after

the Battle of Sagrajas, made responding, for the Taifa emirs, difficult. Soldiers on foot used bows & arrows, sabres, pikes, javelins, each protected by a cuirass of Moroccan leather and iron-spiked shields. During the siege of the fort-town Aledo,

in Murcia, previously captured by the Spaniard Garcia Giménez, ELmoravid and Andalusian hosts are said to have used catapults, in addition to their customary drum beat. Yusef also established naval bases in Cadiz, Almeria and neighboring ports

along the Mediterranean. Ibn Maymun, the governor of Almeria, had a fleet at his disposal. Another such example is the Banu Ghaniya fleet based off the Balearic Islands that dominated the affairs of the western Mediterranean for much of the 12th

century

Siege of Valencia

Although the Elmoravids had not gained much in the way of territory from the Christians, rather than merely offsetting the Reconquista, Yusuf did succeed in capturing Valencia. A city divided between Muslims and Christians, under the weak rule

of a petty emir paying tribute to the Christians, including the famous El Cid, Valencia proved to be an obstacle for the Elmoravid military, despite their untouchable reputation. Abu Bakr ibn Ibrahim ibn Tashfin and Yusef's nephew Abu 'Abdullah

Muhammad both failed to defeat El Cid. Yusef then sent Abu'l-Hasan 'Ali al-Hajj, but he was not successful either. In 1097, on his fourth trip to al-Andalus, Yusef sought to personally dig down and fight the armies of Alfonso VI, making his way

towards the all but abandoned, yet historically important, Toledo. Such a concerted effort was meant to draw the Christian forces, including those laying siege to Valencia, into the center of Iberia. On August 15, 1097, the Almoravids delivered

yet another blow to Alfonso's forces, a battle in which El Cid's son was killed.

Muhammad ibn 'A'isha, Yusef's son, whom he had appointed governor of Murcia, succeeded in delivering an effective pounding to the Cid's forces at Alcira; still not capturing the city, but satisfied with the results of his campaigns, Yusef left

for his court at Marrakesh, only to return two years later in a new effort to take the provinces of eastern al-Andalus. After El Cid died in the same year, 1099, his wife Jimena began ruling until the coming of another Elmoravid campaign at the

tail end of 1100, led by Yusef's trusted lieutenant Mazdali ibn Tilankan. After a seven-month siege, Alfonso and Jimena, despairing of the prospects of staving off the Elmoravids, set fire to the great mosque in anger and abandoned the city.

Yusef had finally conquered Valencia achieving dominance over eastern al-Andalus. He receives mention in the oldest Spanish epic Poema del Cid, also known as El Cantar del Mio Cid.

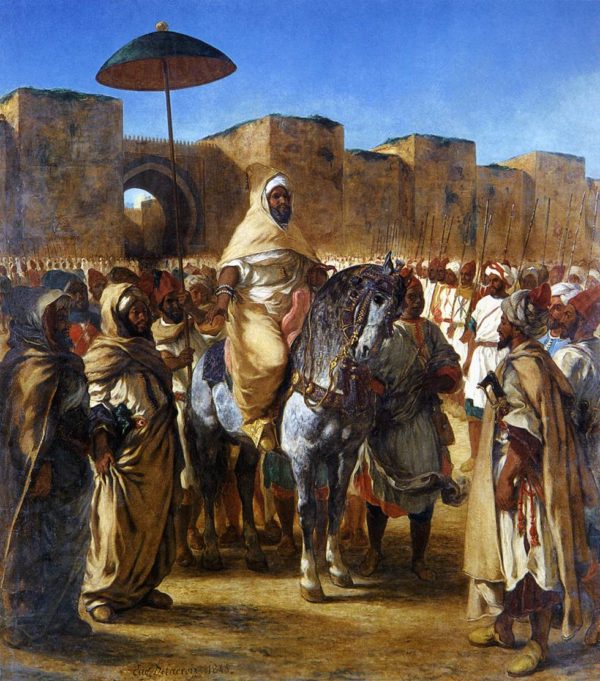

Description and character

A wise and shrewd man, neither too prompt in his determinations, nor too slow in carrying them into effect", Yusef was very much adapted to the rugged terrain of the Sahara and had no interests in the pomp of the Andalusian courts.

According to medieval Arabic writers, Yusuf was of average build and stature. He is further described as having "had a clear brown complexion and he had a thin beard. His voice was soft, his speech elegant. His eyes were black, his nose was

hooked, and he had fat on the fleshy portions of his ears. His hair was curly and his eyebrows met above his nose."

Legacy

His son and successor, Ali ibn Yusuf, was viewed as just as devout a Muslim as his father. Córdoba, in about 1119, served as the launch pad for Andalusian insurrection. Christians on the northern frontier gained momentum shortly after his

father's death, and the Almohads, beginning about 1120, were to engulf the southern frontier. This ultimately led to the disintegration of Yusef's hard-gained territories by the time of Ibrahim ibn Tashfin (1146) and Ishaq ibn Ali (1146–1147),

the last of the Elmoravid dynasty.

While Yusef was the most honorable of Muslim rulers, he spoke Arabic poorly. Ali ibn Yusef in 1135 exercised good stewardship by attending to the University of Al-Karaouine and ordering the extension of the mosque from 18 to 21 aisles, expanding

the structure to more than 3,000 square meters. Some accounts suggest that to carry out this work Ali ibn Yusef hired two Andalusian architects, who also built the central aisle of the Great Mosque of Tlemcen, Algeria, in 1136.

Abdullah ibn Yasin

(1040 -1059) |

Abdallah ibn Yasin (Arabic: عبد الله بن ياسين) (died 7 July 1059 C.E. in "Krifla" near Rommani, present-day Morocco) was a theologian and spiritual leader of the Elmoravid movement

Early life, education and career

Abdallah ibn Yasin was from the tribe of the Jazulah (pronounced Guezula), a Sanhaja sub-tribe from the Sous. A Maliki theologian, he was a disciple of Waggag ibn Zallu al-Lamti and studied in his Ribat, "Dar al-Murabitin" which was located in

the village of Aglu, near present-day Tiznit. In 1046 the Gudala chief Yahya Ibn Ibrahim, came to the Ribat asking for someone to promulgate Islamic religious teachings amongst the Berber of the Adrar (present-day Mauritania) and Waggag ibn Zallu

chose to send Abdallah ibn Yasin with him. The Sanhaja were at this stage only superficially Islamicised and still clung to many heathen practices, and so Ibn Yasin preached to them an orthodox Sunnism.

After a revolt of the Godala he was forced to withdraw with his followers. In alliance with Yahya ibn Umar, the leader of the Lamtuna tribe, he managed to quell the rebellion.

Ibn Yasin now formed the Elmoravid alliance from the tribes of the Lamtuna, the Masufa and the Godala, with himself as spiritual leader and Yahya ibn Umar taking the military command. In 1054 the Maghrawa-ruled Sijilmasa was conquered. Ibn Yasin

introduced his orthodox rule - amongst other things wine and music were forbidden, non-Islamic taxes were abolished and one fifth of the spoils of war were allocated to the religious experts. This rigorous application of Islam soon provoked a

revolt in 1055.

Death

Yahya ibn Umar was killed in 1056 in a renewed revolt of the Gudala in the Sahara, upon which Ibn Yasin appointed Yahya's brother Abu-Bakr Ibn-Umar (1056–1087) the new military leader. Abu Bakr destroyed Sijilmasa, but was not able to force the

Gudala back into the Elmoravid league. He went on to capture Sūs and its capital Aghmat (near modern Marrakech) in 1058.

Ibn Yasin died while attempting to subjugate the Barghawata on the Atlantic coast in 1059. He was replaced by Sulaiman ibn Haddu, who, killed in turn, would not be replaced. His grave is almost due south of Rabat, near Rommani, overlooking

the Krifla River, and is marked on Michelin maps as the marabout of Sidi Abdallah.A mosque and a mausoleum were built on his grave, and the site is still intact today.

l

l

Ibrahim ibn Tashfin

(1145 - 1147) |

Ibrahim ibn Tashfin (Arabic: إبراهيم بن تاشفين) (died 1147) was the seventh Almoravid king, who reigned shortly in 1146–1147. Once the news of the death of his father Tashfin ibn Ali reached Marrakech, he was proclaimed king while still an

infant. He was soon replaced by his uncle Ishaq ibn Ali, but the Almohads quickly subdued Marrakech and killed both

but we may presume them to have been negroid.

an Egyptologist, describes them as “people with distinctive red or blond hair and blue eyes who lived on the edge of the western desert bordering Egypt. According to Gerald Massey, the Egyptians called the Lybians Tamahu. “In Egyptian, Tama means people and created. Hu is white, light ivory. Tamahu are the created white people. The Libyans role in that illuminated epoch of African history was to provide a constant irritant to lower Egypt. Several border skirmishes took place, culminating in extensive raiding during the 6th Dynasty. As DuBois notes, “there came great raids upon the Libyans to the west of Egypt.

Tens of thousands of soldiers, negros particularly from the Sudan, beat this part of the land into subjection.” Sethos, a Pharaoh in the 18th Dynasty, again confronted the Libyan foe and subdued them.

an Egyptologist, describes them as “people with distinctive red or blond hair and blue eyes who lived on the edge of the western desert bordering Egypt. According to Gerald Massey, the Egyptians called the Lybians Tamahu. “In Egyptian, Tama means people and created. Hu is white, light ivory. Tamahu are the created white people. The Libyans role in that illuminated epoch of African history was to provide a constant irritant to lower Egypt. Several border skirmishes took place, culminating in extensive raiding during the 6th Dynasty. As DuBois notes, “there came great raids upon the Libyans to the west of Egypt.

Tens of thousands of soldiers, negros particularly from the Sudan, beat this part of the land into subjection.” Sethos, a Pharaoh in the 18th Dynasty, again confronted the Libyan foe and subdued them.

(Morocco and Algeria) were peopled by black Africans, also called Moors by the Romans and later by the Europeans.

but some of which is preserved, is African in origin and character. Its grammar is identified with the Abyssinian” (Abyssinia being another name for Ethiopia). Finally, Houston quotes the Encyclopedia Britannica's article on Arabia; “The inhabitants of Yemen, Hadramaut, Oman and the adjoining districts [in Arabia], in shape of head, color, length and slenderness of limbs and scantiness of hair, point to an African origin. Stone engravings thousands of years old as well as modern photographs of Arabians bear testimony to the black African characteristics bequeathed Arabia by the original Arabians, the Cushite Ethiopians. According to Houston, “The culture of the Saracens and Islam arose and flourished from ingrafting Semitic blood upon the older Cushite root. As may be expected, W. E. B. DuBois makes some interesting points regarding the use of the word “Arab.” Having noted that many Arabs are “darkskinned, sometimes practically black, often have Negroid features, and hair that may be Negro in quality,” DuBois reasons that “the Arabs were too nearly akin to Negros to draw an absolute color line

Finally, DuBois concludes that the expression Arab has evolved into a definition that is more religious than racial. “The term Arab is applied to any people professing Islam, . . . much race mixing has occurred, so that while the term has a cultural value it is of little ethnic significance and is often misleading. In his native Arabia, Mohamet rallied great numbers of warriors and set out to subdue the east. Mohamet’s death in 632 A.D. did not stop the tremendous onslaught of his Arabian knights. They would eventually reach west to the Atlantic Coast of Africa, northwest to France and Spain, north to Russia and east to India. The jihads or crusades through north Africa claimed Egypt in 638, Tripoli in 643 and southwest Morocco in 681. With the bulk of north Africa united in the name of Allah, Mohamet’s followers looked north to Iberia, “land of rivers,” now known as Spain and Portugal. The Arab followers of Mohamet had found converts among the African Moors, both black and tawny, and both Arab and Moorish officers were later to lead the predominantly Moorish soldiers into Iberia. In fact, the followers of Mohamet amassed their greatest armies and some of their most outstanding military leaders from the Moors.

but some of which is preserved, is African in origin and character. Its grammar is identified with the Abyssinian” (Abyssinia being another name for Ethiopia). Finally, Houston quotes the Encyclopedia Britannica's article on Arabia; “The inhabitants of Yemen, Hadramaut, Oman and the adjoining districts [in Arabia], in shape of head, color, length and slenderness of limbs and scantiness of hair, point to an African origin. Stone engravings thousands of years old as well as modern photographs of Arabians bear testimony to the black African characteristics bequeathed Arabia by the original Arabians, the Cushite Ethiopians. According to Houston, “The culture of the Saracens and Islam arose and flourished from ingrafting Semitic blood upon the older Cushite root. As may be expected, W. E. B. DuBois makes some interesting points regarding the use of the word “Arab.” Having noted that many Arabs are “darkskinned, sometimes practically black, often have Negroid features, and hair that may be Negro in quality,” DuBois reasons that “the Arabs were too nearly akin to Negros to draw an absolute color line

Finally, DuBois concludes that the expression Arab has evolved into a definition that is more religious than racial. “The term Arab is applied to any people professing Islam, . . . much race mixing has occurred, so that while the term has a cultural value it is of little ethnic significance and is often misleading. In his native Arabia, Mohamet rallied great numbers of warriors and set out to subdue the east. Mohamet’s death in 632 A.D. did not stop the tremendous onslaught of his Arabian knights. They would eventually reach west to the Atlantic Coast of Africa, northwest to France and Spain, north to Russia and east to India. The jihads or crusades through north Africa claimed Egypt in 638, Tripoli in 643 and southwest Morocco in 681. With the bulk of north Africa united in the name of Allah, Mohamet’s followers looked north to Iberia, “land of rivers,” now known as Spain and Portugal. The Arab followers of Mohamet had found converts among the African Moors, both black and tawny, and both Arab and Moorish officers were later to lead the predominantly Moorish soldiers into Iberia. In fact, the followers of Mohamet amassed their greatest armies and some of their most outstanding military leaders from the Moors.

Although he cast covetous eyes towards Iberia, he

hesitated, knowing that a campaign on Iberia could exhaust his armies. The

Visigoths, who had earlier toppled the Roman Empire in Iberia, had ruled for over two hundred years. The Visigoths were a vigorous, rather barbaric people

who, as Christians, believed in religious compensation for their vices. Over

time they had become “quite as corrupt and immoral as the Roman nobles

who had preceded them.

Although he cast covetous eyes towards Iberia, he

hesitated, knowing that a campaign on Iberia could exhaust his armies. The

Visigoths, who had earlier toppled the Roman Empire in Iberia, had ruled for over two hundred years. The Visigoths were a vigorous, rather barbaric people

who, as Christians, believed in religious compensation for their vices. Over

time they had become “quite as corrupt and immoral as the Roman nobles

who had preceded them.

It will be easy to turn this table on him if you will but risk death for one instance."

It will be easy to turn this table on him if you will but risk death for one instance."

The site had been chosen and work started by Abu Bakr in 1070. The work was completed by Yusef, who then made it the capital of his empire, in place of the former

capital Aghmāt. By the time Abu Bakr died in 1087, after a skirmish in the Sahara as the result of a poison arrow, Yusef had crossed over into al-Andalus and also achieved victory at the Battle of az-Zallaqah, also known as the Battle of Sagrajas

in the west. He came to al-Andalus with a force of 15,000 men, armed with javelins and daggers, most of his soldiers carrying two swords, shields, cuirass of the finest leather and animal hide, and accompanied by drummers for psychological effect.

Yusef's cavalry was said to have included 6,000 shock troops from Senegal mounted on white Arabian horses. Camels were also put to use. On October 23, 1086, the Elmoravid forces, accompanied by 10,000 Andalusian fighters from local Muslim

provinces, decisively checked the Reconquista, significantly outnumbering and defeating the largest Christian army ever assembled up to that point. The death of Yusef's heir, however, prompted his speedy return to Africa.

When Yusuf returned to al-Andalus in 1090, he saw the lax behavior of the taifa kings, both spiritually and militarily, as a breach of Islamic law and principles, and left Africa with the express purpose of usurping the power of all the Muslim

principalities, under the auspices of the Abbasid caliph of Baghdad, with whom he had shared correspondence, and under the slogan "The spreading of righteousness, the correction of injustice and the abolition of unlawful taxes." The emirs in such

cities as Seville, Badajoz, Almeria and Granada had grown accustomed to the extravagant ways of the west. On top of doling out tribute to the Christians and giving Andalusian Jews unprecedented freedoms and authority, they had levied burdensome

taxes on the populace to maintain this lifestyle. After a series of fatwas and careful deliberation, Yusef saw the implementation of orthodoxy as long overdue. That year, he exiled the emirs 'Abdallah and his brother Tamim from Granada and Málaga,

respectively, to Aghmāt, and a year later al-Mutamid of Seville suffered the same fate. When all was said and done, Yusef united all of the Muslim dominions of the Iberian Peninsula, with the exception of Zaragoza, to the Kingdom of Morocco, and

situated his royal court at Marrakech. He took the title of Amir al-muslimin (Prince of the Muslims), seeing himself as humbly serving the caliph of Baghdad, but to all intents and purposes he was considered the caliph of the western Islamic

empire. The military might of the Elmoravids was at its peak.

The Sanhaja confederation, which consisted of a hierarchy of Lamtuna, Musaffa and Djudalla Berbers, represented the military's top brass. Amongst them were Andalusian Christians and heretic Africans, taking up duties as diwan al-gund, Yusef's own

personal bodyguard, including 2,000 black horsemen, whose tasks also included registering soldiers and making sure they were compensated financially. The occupying forces of the Almoravids were made up largely of horsemen, totaling no less than

20,000. Into the major cities of al-Andalus, Seville (7,000), Granada (1,000), Cordoba (1,000), 5,000 bordering Castile and 4,000 in western al-Andalus, succeeding waves of horsemen, in conjunction with the garrisons that had been left there after

the Battle of Sagrajas, made responding, for the Taifa emirs, difficult. Soldiers on foot used bows & arrows, sabres, pikes, javelins, each protected by a cuirass of Moroccan leather and iron-spiked shields. During the siege of the fort-town Aledo,

in Murcia, previously captured by the Spaniard Garcia Giménez, ELmoravid and Andalusian hosts are said to have used catapults, in addition to their customary drum beat. Yusef also established naval bases in Cadiz, Almeria and neighboring ports

along the Mediterranean. Ibn Maymun, the governor of Almeria, had a fleet at his disposal. Another such example is the Banu Ghaniya fleet based off the Balearic Islands that dominated the affairs of the western Mediterranean for much of the 12th

century

The site had been chosen and work started by Abu Bakr in 1070. The work was completed by Yusef, who then made it the capital of his empire, in place of the former

capital Aghmāt. By the time Abu Bakr died in 1087, after a skirmish in the Sahara as the result of a poison arrow, Yusef had crossed over into al-Andalus and also achieved victory at the Battle of az-Zallaqah, also known as the Battle of Sagrajas

in the west. He came to al-Andalus with a force of 15,000 men, armed with javelins and daggers, most of his soldiers carrying two swords, shields, cuirass of the finest leather and animal hide, and accompanied by drummers for psychological effect.

Yusef's cavalry was said to have included 6,000 shock troops from Senegal mounted on white Arabian horses. Camels were also put to use. On October 23, 1086, the Elmoravid forces, accompanied by 10,000 Andalusian fighters from local Muslim

provinces, decisively checked the Reconquista, significantly outnumbering and defeating the largest Christian army ever assembled up to that point. The death of Yusef's heir, however, prompted his speedy return to Africa.

When Yusuf returned to al-Andalus in 1090, he saw the lax behavior of the taifa kings, both spiritually and militarily, as a breach of Islamic law and principles, and left Africa with the express purpose of usurping the power of all the Muslim

principalities, under the auspices of the Abbasid caliph of Baghdad, with whom he had shared correspondence, and under the slogan "The spreading of righteousness, the correction of injustice and the abolition of unlawful taxes." The emirs in such

cities as Seville, Badajoz, Almeria and Granada had grown accustomed to the extravagant ways of the west. On top of doling out tribute to the Christians and giving Andalusian Jews unprecedented freedoms and authority, they had levied burdensome

taxes on the populace to maintain this lifestyle. After a series of fatwas and careful deliberation, Yusef saw the implementation of orthodoxy as long overdue. That year, he exiled the emirs 'Abdallah and his brother Tamim from Granada and Málaga,

respectively, to Aghmāt, and a year later al-Mutamid of Seville suffered the same fate. When all was said and done, Yusef united all of the Muslim dominions of the Iberian Peninsula, with the exception of Zaragoza, to the Kingdom of Morocco, and

situated his royal court at Marrakech. He took the title of Amir al-muslimin (Prince of the Muslims), seeing himself as humbly serving the caliph of Baghdad, but to all intents and purposes he was considered the caliph of the western Islamic

empire. The military might of the Elmoravids was at its peak.

The Sanhaja confederation, which consisted of a hierarchy of Lamtuna, Musaffa and Djudalla Berbers, represented the military's top brass. Amongst them were Andalusian Christians and heretic Africans, taking up duties as diwan al-gund, Yusef's own

personal bodyguard, including 2,000 black horsemen, whose tasks also included registering soldiers and making sure they were compensated financially. The occupying forces of the Almoravids were made up largely of horsemen, totaling no less than

20,000. Into the major cities of al-Andalus, Seville (7,000), Granada (1,000), Cordoba (1,000), 5,000 bordering Castile and 4,000 in western al-Andalus, succeeding waves of horsemen, in conjunction with the garrisons that had been left there after

the Battle of Sagrajas, made responding, for the Taifa emirs, difficult. Soldiers on foot used bows & arrows, sabres, pikes, javelins, each protected by a cuirass of Moroccan leather and iron-spiked shields. During the siege of the fort-town Aledo,

in Murcia, previously captured by the Spaniard Garcia Giménez, ELmoravid and Andalusian hosts are said to have used catapults, in addition to their customary drum beat. Yusef also established naval bases in Cadiz, Almeria and neighboring ports

along the Mediterranean. Ibn Maymun, the governor of Almeria, had a fleet at his disposal. Another such example is the Banu Ghaniya fleet based off the Balearic Islands that dominated the affairs of the western Mediterranean for much of the 12th

century

l

l